One of my goals for the year is to gain a basic proficiency with some weapon platforms that are unfamiliar to me, one of these being the traditional, double action pistol. These are the pistols that were so popular in the nineties, where the first pull of the trigger cocks the hammer and fires the round, much like a double action revolver. To fire subsequent rounds, the hammer was cocked by the slide, making the trigger pull closer to the short, light pull of a single action pistol.

Popular examples are the Smith and Wesson 5900 series pistols, which were adopted by many law enforcement agencies before the Glock became dominant in that market, and, of course, the M9, which was the official pistol of our armed services from 1990 until 2017.

A couple of years ago, I found a police trade- in Beretta 92, which is the civilian version of the M9. I picked it up because it was a good deal, and because anything John McClane carried had to be good, right? However, since buying it, I haven’t put more than a box of ammo through it. I decided it was high time to change that.

anything John mcclane carried has to be good, right?

The traditional double actions are famously difficult to master. Jeff Cooper once compared shooting a double action it to swimming the English Channel without flippers; it is possible, but not easy. I think the colonel was speaking in hyperbole when he said that, but it underscores the truth: this is not an easy system to learn.

My goal with this project is not to achieve mastery, which would take more time than I am willing to invest at this time. My goal is to gain a basic level of skill with a system that is common, if not widely used anymore.

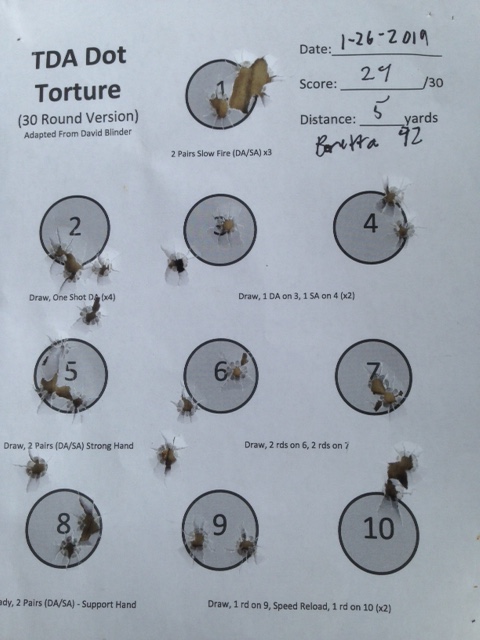

The chief difficulty with the TDA, is that you will have to learn two different trigger pulls. To work on this, I used a version of the popular dot torture test made for this platform.

Dot-Torture-30-rd-version-small-dots-TDA

I found this to be a good drill for learning the trigger of the TDA. After running it a couple of times, I felt ready to move on to some timed drills.

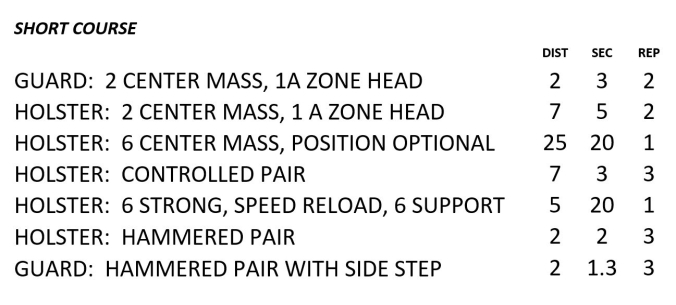

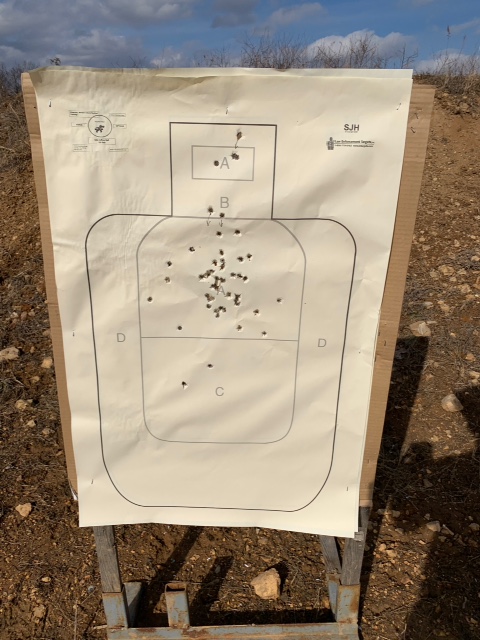

I decided to run the Hojutsu Short course. Based on the Alaska State Troopers Pistol Qualification, it is a well- rounded course covering a variety of practical skills, but using time allowances generous enough not to dissuade a beginner.

I ran this twice, and was able to score 90% on the second attempt. Col. Cooper was right; this is a difficult gun to shoot in many ways, the trigger inconsistency being the greatest hangup. That being said, the pistol was extremely accurate. Recoil was as mild as I have ever experienced in a pistol, and I did not experience a single malfunction, even using some hand loads that my glock refused to eat.

One problem I had concerned the safety mechanism, so I did some research, and wrote to Jeff Hall explaining my difficulty.

He replied: “I carried a S&W double/single action, the 4006, for ten years with the Troopers. S&W does not call it a safety, they call it a de-cocker.

We did it just like John says. The gun is carried with a round in the chamber, de-cocked, with the de-cocker in the up (off safety) position. So, draw, point in, shoot as needed, decock as you come to guard, tac load and holster. It’s the same thing as a double-action revolver.”

When I shoot this gun next, I will try this method. It would have saved me a couple of overtime penalties, when I forgot to lift the decocker, and dropped the hammer on the safety bar.

If you are looking to gain some basic familiarity with a TDA pistol, give the course of fire I describe here a try. You can shoot the Dot Torture and the Short course twice, and still only burn 156 rounds.

For more on the TDA pistol, I highly recommend John Farnam’s book, “Defensive Handgunning”.

Accuracy was good with the Beretta, but my unfamiliarity with the trigger cost a couple of over- times.

I started teaching my children baseball this summer, just the basics: How to throw and catch a ball. It got me thinking about the process of learning the basics.

I started teaching my children baseball this summer, just the basics: How to throw and catch a ball. It got me thinking about the process of learning the basics.

Show any twelve- year- old in America a set of nunchaku, a kama, or a tonfa, and ask him what they are, and you will get an enthusiastic reply: “Karate weapons!” I remember watching a Bruce Lee movie with my wife, who commented, “If I were fighting that many bad guys, I think I would find a better weapon than a nunchaku.” My wife was certainly correct. The nunchaku isn’t a very good weapon; in fact, it isn’t a weapon at all.

Show any twelve- year- old in America a set of nunchaku, a kama, or a tonfa, and ask him what they are, and you will get an enthusiastic reply: “Karate weapons!” I remember watching a Bruce Lee movie with my wife, who commented, “If I were fighting that many bad guys, I think I would find a better weapon than a nunchaku.” My wife was certainly correct. The nunchaku isn’t a very good weapon; in fact, it isn’t a weapon at all.