A wise man once told me, “If you want to be a leader, you have to be a reader”.

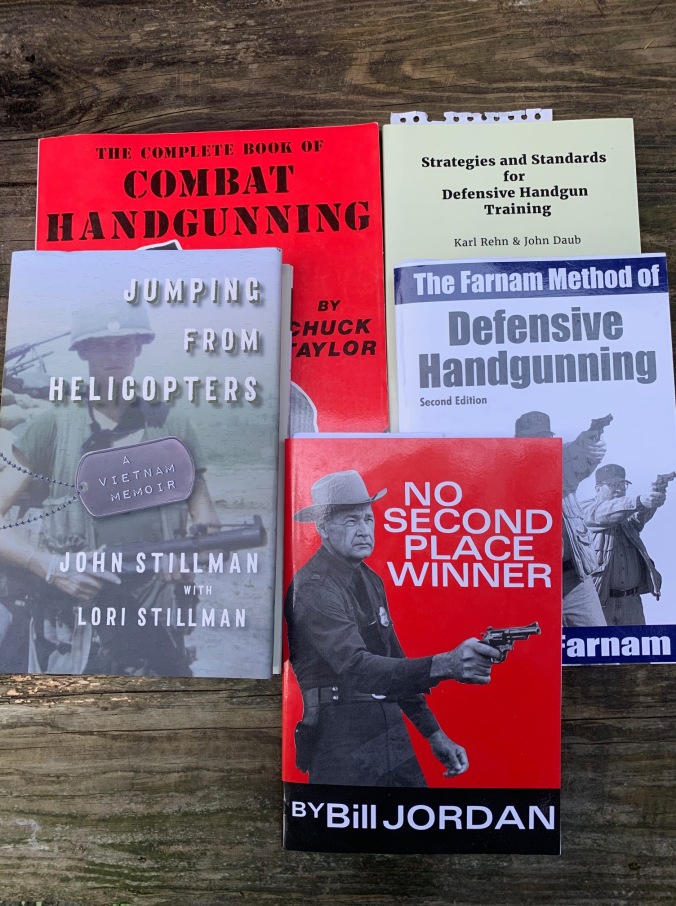

I have found this good advice. Here are some of the books I have been reading lately, not necessarily in any type of order.

No Second Place Winner, by Bill Jordan, published in 1965. This is a classic that everyone should read. You will find lots of pictures of Jordan shooting one- handed, from the hip, pipe in his mouth, and cowboy hat firmly on his head. Shooting styles surely have changed, but there is no getting around the fact that this man was an expert with a handgun, who had shot his way out of more than a couple of scrapes in his day. Interestingly, for all the emphasis on shot- from- the- hip fast draw, Jordan recommends bringing the gun up into the line of sight at distances of seven yards and greater (as Applegate did with his point shooting method), and actually using the sights beyond 15 yards. This book has lots of quotable passages, but my favorite is: “For ninety percent of your practice, draw from the holster, and fire one shot. It’s that first shot that’s important, and it is the one that is most difficult to place accurately.” True words.

The Complete Book of Combat Handgunning, By Chuck Taylor, published in 1982. This really is a comprehensive book, covering gear and ammunition selection, weapon maintenance tactics, and strategy. Taylor is one of the influential shooters from the early days of the Modern Technique of the pistol, and despite what a lot of current trainers like to say about the gun fighting in the post 9-11 world, not much has changed from the techniques Taylor demonstrates in this book (with excellent photographs). The same cannot be said for handguns, ammunition, and holsters, all of which have improved considerably from the selection that was available in 1982. The best part of this book, to me, is the section of recommended dryfire and live fire drills. He recommends 30-45 minutes of dry practice, daily. He considers this a basic level, for more advanced practice, he adds an additional 20 minutes daily. The live fire drills are challenging, and I would urge anyone who is serious about the pistol to find this book, and try the drills. Chuck Taylor went on to develop the Hand Gun combat master certification which is near legendary in its difficulty.

If Jordan and Taylor were interested in mastering the pistol, Karl Rehn and Jon Daub are at the opposite spectrum, with their newly published book, Strategies and Standards for Defensive Handgun Training. Rehn and Daub recognize that far from spending 45 minutes a day dry practicing with their hand guns, or practicing fast draw by shooting up thousands of specially hand loaded, paraffin wax projectiles, (as Jordan recommends) most civilian pistol carriers will, at best, show up for one, four- hour class per year. Rehn and Daub try to establish what a minimum standard of skill should be, and how to get a student to that level, in the time that they are willing to spend. This book is a trove of good information, filled with useful statistics. They even make an attempt to categorize the difficulty level of various common drills. As much as I like this book, it could have used a better editor. The information is a bit disorganized, and they have an annoying habit of referencing a drill, but not describing it, advising readers to “look it up on the internet”. If I wanted to do that, I wouldn’t have had to buy the book, not to mention that many drills are not standardized, and it is difficult to know if the version of, say, the “Casino drill”, which you can find online, is the same one that the authors are referencing. If you do any handgun instruction at all, you should read this book; if you don’t teach, you probably won’t find it interesting.

I like to read a lot of first person accounts by regular G.I.s, and Jumping From Helicopters, by John Stillman, is just one of the most recent I have found. It contains a good, firsthand account of a paratrooper in Vietnam.

The Farnam Method of Defensive Handgunning, By John S. Farnam, published in 2000, is yet another gun-fighting manual, but it contains very little information that is redundant to the similar books I have already mentioned here. Aside from excellent coverage of gun handling and self- defense, this book covers: dealing with law enforcement, confronting criminals, use- of- force considerations, and even touches on first aid. The best part, for me, was Farnam’s extensive coverage of the traditional, double action pistol; a system that doesn’t get much coverage from serious gun writers, in spite of its popularity with police and militaries around the world. Farnam loves charts, comparing the various attributes of different pistols and ammunitions, and I found the chart comparing the workings of various traditional, double action pistols to be quite enlightening. Many of these systems are very different from each other, in spite of being classified as the same.

If you are interested in a deeper dive into military history, Martin Van Creveld’s The Culture of War, and his History of Strategy: From Sun Tzu to William S. Lind, are a pair of books that I have recently read. Van Creveld writes succinctly, with an easy- to- read style, which, layman though I am, I found easy to understand. His books are filled with a dry humor (at one point, he refers to T. E. Lawrence as “a typical British Eccentric”). I have only recently discovered this author, and plan to read more of his works in the future.

Another recent discovery, for me, is Tony Hillerman, who wrote detective fiction set on the Navajo reservation, and starring Lieutenant Joe Leaphorn. The mysteries are clever, the characters interesting, and Hillerman weaves in a lot of detail about Navajo culture, history, and religion that I find fascinating. I’ve read four of these, and immensely enjoyed every one, although Sacred Clowns is my favorite so far.

I know a lot of people who have snobbish disdain for fiction, usually characterizing their thoughts by saying, with words or demeanor, “I only have time to read serious books.” This attitude is as sophomoric as it is stupid. Oftentimes, more truth can be conveyed in a good work of fiction, than in an entire library of technical manuals, so don’t be ashamed to mix a little quality fiction into your reading.

We have more written material available to us than at any previous time in history, anything you want to know, someone has written a book about it. While there is no substitute for hands on experience, we can gain a huge leg up by reading about the work of those who have gone before us.

I started teaching my children baseball this summer, just the basics: How to throw and catch a ball. It got me thinking about the process of learning the basics.

I started teaching my children baseball this summer, just the basics: How to throw and catch a ball. It got me thinking about the process of learning the basics.

Not long ago, nearly all the experts on firearms recommended carrying at least one reload. With the advent of greater magazine capacity and more reliable firearms, the advice on how much ammunition to carry has shifted, some of the current experts don’t recommend carrying a reload at all. However, an experience I had at a recent force- on- force exercise with One Shepherd made me think of a reason for carrying a reload that I had never heard expounded by the experts.

Not long ago, nearly all the experts on firearms recommended carrying at least one reload. With the advent of greater magazine capacity and more reliable firearms, the advice on how much ammunition to carry has shifted, some of the current experts don’t recommend carrying a reload at all. However, an experience I had at a recent force- on- force exercise with One Shepherd made me think of a reason for carrying a reload that I had never heard expounded by the experts.