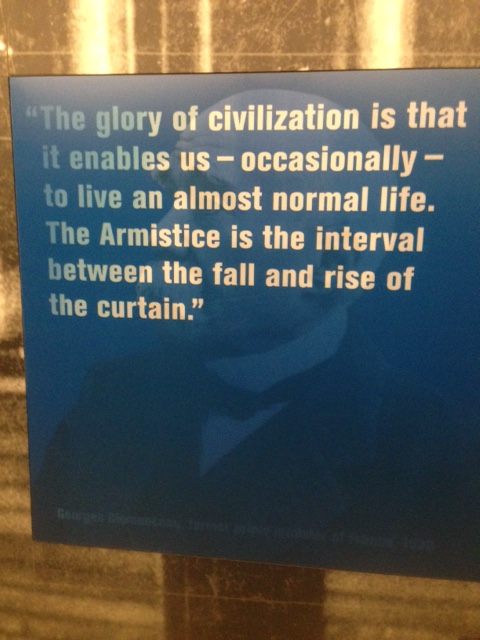

“During the whole affair, the rebels attacked us in a very scattered, irregular manner, but with perseverance and resolution, nor did they ever dare to form into any regular body. Indeed they knew too well what was proper, to do so. Whoever looks upon them as an irregular mob, will find himself very much mistaken. They have men among them who know very well what they are about.” -Lord Hugh Percy, after the battle of Lexington.

Since time immemorial, men have understood that a team of men will defeat a mob, even if the mob is comprised of men who are superb individual fighters. This is largely why the Romans defeated Spartacus’s revolt, and the colonial powers defeated so many nineteenth- century tribesmen. The question I am interested in, in this post, is not whether a team is superior, but how should it be composed, and in what number.

With a two- element team, you have fire and maneuver capability. One element can fire while the other moves, bounding either forward (for the attack), backward (to break contact), or laterally (to flank).

The smallest possible number of people you can have, and still be called a team, is of course two. For that reason, the buddy team is foundational for soldiers and cops everywhere. The weakness of the buddy team is that it has severely limited fire power, with only one person to lay down suppressive fire, while the second moves. One man can only easily cover a sector about 45 degrees wide. A dispersed enemy will require more people to suppress. Moreover, the buddy team is fragile, being only one casualty or weapon malfunction away from a single warrior.

Far greater fire power and survivability is found in the four man fire team. Not only does the fire team lay down twice as many rounds and suppress twice as wide an area, but it has the man power to continue function as a team, even if as many of two of its members are out of action. Then, having cleared the area of enemy fighters, one team member can administer aid to the injured, while the other provides a security over- watch. Even the old Boy Scout manual recommended a minimum of four boys for a backwoods hike. In case of injury, one could stay with the injured party, while two went for help.

A great deal can be accomplished with a four man fire team, but still, you are limited. It just doesn’t have much mass, especially when divided into two maneuver elements. The next step up in organization would be the eight man squad, which is commonly used by the U.S. Army. In this configuration, with each fire team acting as an independent maneuver element, we start to see how truly functional a small unit can be. It is not just a matter of eight men being twice as good as four. At these numbers, we start to reach a critical mass, where the whole begins to be much more than the sum of its parts.

Even so, with only two elements, you are limited to simple bounding maneuvers. Most battle drills, whether raid, ambush, or deliberate attack, call for three elements: Assault, Support and Security. In area defense, this breaks down into line, reserve and screening activities; still three elements. Even the ancient Roman army was divided into three elements; Hastati, Principes, Triarii.

If our basic unit is the fire team, this gives us a twelve man squad, as is commonly deployed by the USMC.

To say twelve is better than eight, is not a simple matter of “more is better”. A twelve man squad fills every task at a minimum level, and achieves a synergy that is difficult with smaller numbers.

All well and good, but what if you don’t have twelve men? Obviously, you will have to make adjustments. To paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld, you go to war with the team you have, not the team you want. First, consider your mission. Are you tasked with reconnaissance? If your goal is not to make hard contact with the enemy (in other words see him without him seeing you), you may be better served by a smaller team. Smaller teams are easier to hide, and, as we pointed out earlier, two elements are all that is necessary to break contact if things go sour. One of the classic examples of a tiny recon team would be a scout sniper team, consisting of a sniper and his spotter. (While sniper teams are famous for taking out high value targets on the battle field, their value for scouting and reconnaissance, is often more important.)

Another approach is to intentionally neglect one of the elements. For instance, if you are shorthanded, you may decide to task all of your meager resources to assault and support, and none to security. While this is inherently dangerous, and there are many examples of commanders doing this to their peril, there are cases in history where commanders have used heavy violence of action and a rapid operational tempo in lieu of flank security. In other words, they have attacked with enough vigor that the enemy is constantly on his heels, and too unbalanced to launch a counterattack.

Finally, you can scale your mission down. Imagine this tiny, six man ambush: One buddy team is the attack, one is support, and the third is split into two lonely, one man flank security elements. With teams this small, every man must be utterly dependable. There is no one to wake up a drowsy sentinel, and it is difficult to mix in new troops with less experience, when the numbers are this small, without seriously diluting your fighting ability.

Lastly, you can alter your tactics. Outnumbered forces have historically employed far ambushes, baited ambushes, reverse slope defenses, booby traps, and sabotage.

If you are a man who knows very much what you are about you can transform your irregular mob into an effective team.